It has taken me even longer than expected to find the time to write about this 800 page award winning biography about one of the famous "robber barons" of the late 19th and early 20th century. I read this book as part of my ongoing effort to read through the books that I already own recognizing that I am still going to buy new books and/or borrow from libraries. I bought the book for two reasons - my interest in this group of business pioneers/philanthropists and my interest in biography as a literary form. While writing plans are always subject to change (and frequently) I am very much leaning towards writing a biography after Paul and I finish our book about Ebbets Field. Part of my interest in that project was to explore the possibility of a biography of Charles Ebbets and everything I have found suggests that he is a worthy topic.

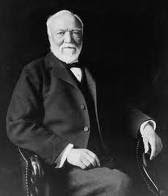

Ebbets, of course, is no where near in the same league (baseball or otherwise) with someone like Andrew Carnegie. Reportedly at one time the wealthiest man in the world, this Scottish immigrant made his money in the steel industry and then set about giving it away. His philosophy was to make as much money as possible, but then to give it all away before death so the next generation would not be "burdened" by great wealth. From a business standpoint Carnegie is interesting because unlike may of his peers (if there was such a thing), he did no work long hours at his business. Almost as soon as he had enough money Carnegie became detached from the every day aspects of business, preferring to work through subordinates who included people like Henry Clay Frick and Charles Schwab.

While his work habits may not have matched those of John D. Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, he had a similar attitude towards the working man - trying to minimize labor costs and to oppose any efforts at collective bargaining. In Carnegie's case this took its extreme form in the Homestead Steel strike where violence resulted in government intervention. Tragic and most likely unnecessary in its own right, Nasaw's description of these events suggested that what was even more tragic was how the people of Homestead (effectively a company town) actually felt an identification with the business which was all the more reason they resisted management's efforts that would have driven many of them not only out of their jobs, but also their homes. Carnegie's life long effort to portray himself as a someone who closely identified with th working man because he was one of them was more than a little self deceptive.

Ultimately Carnegie and his partners sold out their ownership interest into a new entity called U.S.Steel. Carnegie took his huge share in corporate bonds backed by gold which was probably as good a quality investment as you could get in those days. He then set about giving those bonds away to a number of worthy causes that were of interest to him. Libraries were always a priority for him and many towns throughout the U.S. got their first library through one of these grants - I know that the library in the next town over, Caldwell, NJ, is a Carnegie library and I believe the Verona library is as well. Reading about these gifts in the book, it appears that Carnegie through a trusted subordinate relied on a formula type approach where communities that met the criteria pretty much got their library automatically.

During his lengthy retirement, Carnegie's primary interest, perhaps almost an obsession was world peace. He advocated constantly for arbitration for international disputes and for other measures to promote peace in an increasing belligerent world. Because of his great wealth and connections, he had access to every U. S. President as well as other world leaders. He used this access constantly, but in what frequently seemed to be an incredibly naive way, always thinking he was making more progress than he was. His fears about what the next major war proved to be all to accurate beginning in 1914. In some ways Carnegie was an almost Cassandra like prophet - correctly forseeing what would happen, but unable to get enough people or the right people to believe him.

The book is clearly exhaustively researched and very well written, one that was a relative quick read given its length. My one negative reaction has to do with with something that I heard Robert Caro say in an intereview on CSPN about how he writes his biographies. When he is ready to start writing, Mr. Caro sits down and spends a great deal of time writing one or at the most two paragraphs that say what the book is about. Among other things this facilitates coming back to those main themes no matter what the diversion and no matter how necessary it was. At some times I though this book could have benefited from something like that - in some ways it told the story of the life, but it could have been more focused about the conclusions it was drawing from that life. None of this is to regret not just reading the book, but buying it as well. And as hoped all of this gave me more to think about as I consider a possible biography of Charles Ebbets.

No comments:

Post a Comment